OUR HISTORY

BEGINNING OF TOURISM IN NEW ZEALAND

Local Tribe: Te Arawa

Subtribes: Tuhourangi and Ngati Rangatihi

For many generations the Tuhourangi and Ngati Rangatihi people lived in the shadow of Mount Tarawera, the enigmatic mountain that looms above the lake of the same name.

In the 1840’s-80’s Lake Rotomahana was the focus of a 19th century tourist boom. Rotomahana was the site of a spectacular geothermal phenomenon – a vast expanse of silica formations that became world famous as the Pink and White Terraces.

PINK AND WHITE TERRACES

The Pink Terrace, or Te Otukapuarangi (“The fountain of the clouded sky” in Māori) and the White Terrace, also known as Te Tarata (“the tattooed rock”) were one of New Zealand natural wonders. They were reportedly the largest silica sinter deposits on earth.

The Pink and White Terraces were formed by upwelling geothermal springs containing a cocktail of silica-saturated, near-neutral pH chloride water. These two world-famous springs were part of a group of hot springs and geysers mainly along an easterly ridge named Pinnacle Ridge (or the Steaming Ranges by Mundy). The main tourist attractions included Ngahapu, Ruakiwi, Te Tekapo, Waikanapanapa, Whatapoho, Ngawana, Koingo and Whakaehu.

The Pink and the White Terrace springs were around 1,200 metres (3,900 ft) apart. The White Terrace was at the north-east end of Lake Rotomahana and faced west to northwest at the entrance to the Kaiwaka Channel and descended to the lake edge around 25 metres (82 ft) below. The Pink Terrace lay four fifths of the way down the lake on the western shore facing east to south-east. The pink appearance over the mid and upper basins (very like the colour of a rainbow trout) was due to antimony and arsenic sulfides, although the Pink Terrace also contained gold in ore-grade concentrations.

Formation of the Terraces

The Pink and White Terraces are thought to be over 1,000 years old. The hydrothermal system which powered them may be up to 7,000 years old. The silica precipitation formed many pools and steps over time and formed attractive swimming places.

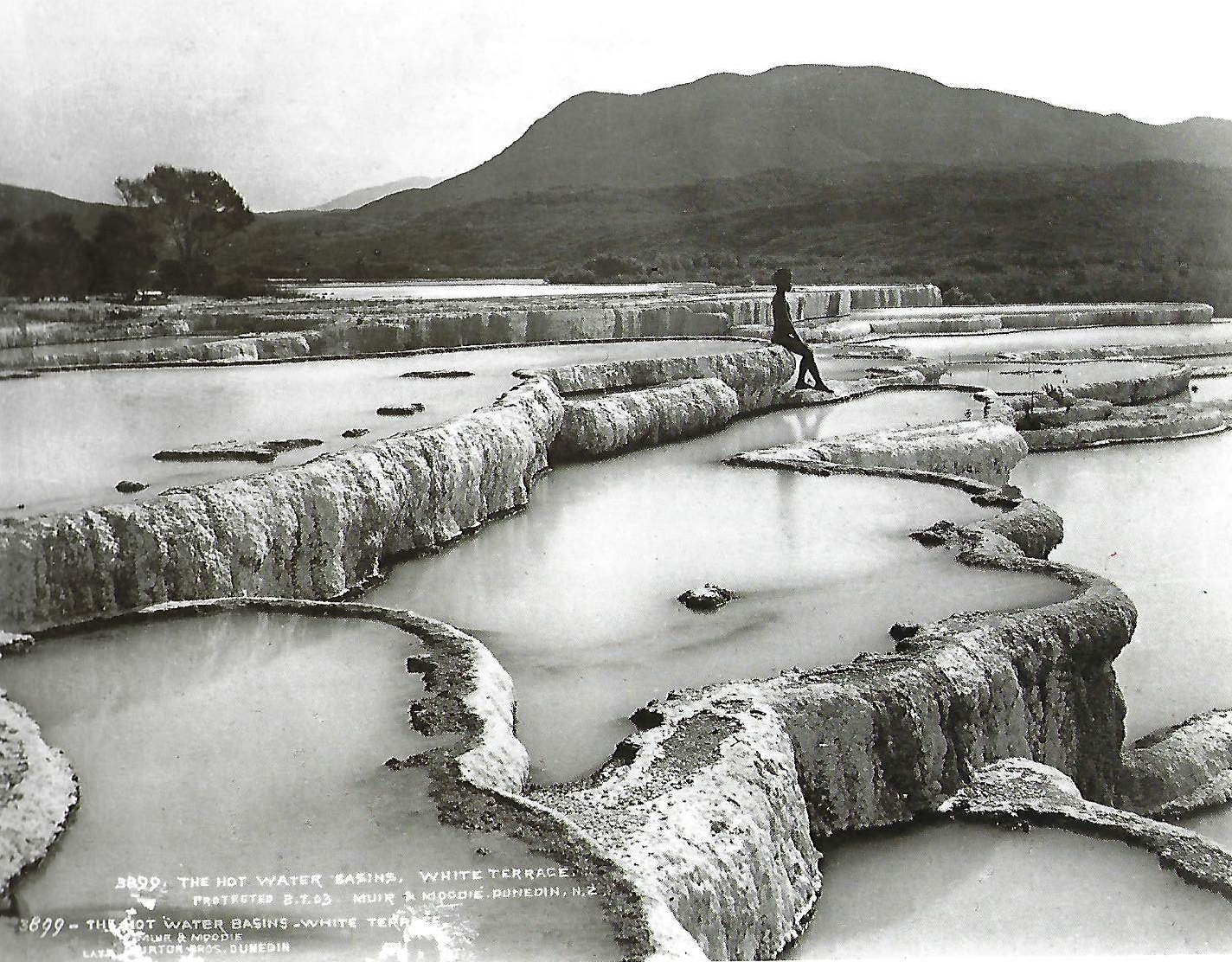

The White Terrace (Te Tarata)

The White Terrace was the larger formation, covering about 8 hectares (20 acres) and descending over about 50 layers and 25 metres (82 ft).

The Pink Terrace (Te Otukapuarangi)

The Pink Terrace descended about 100 metres (330 ft) The top layer was 75–100 metres (246–328 ft) wide and the bottom about 27 metres (89 ft) wide. Tourists preferred to bathe in the upper Pink Terrace pools, because they were clear with a range of temperature and depths.

Becoming Famous

One of the first Europeans to visit Rotomahana was Ernst Dieffenbach. He briefly visited the lake and Terraces while on a survey for the New Zealand Company in early June 1841. The description of his visit in his book “Travels in New Zealand” inspired an international interest in the Pink and White Terraces.

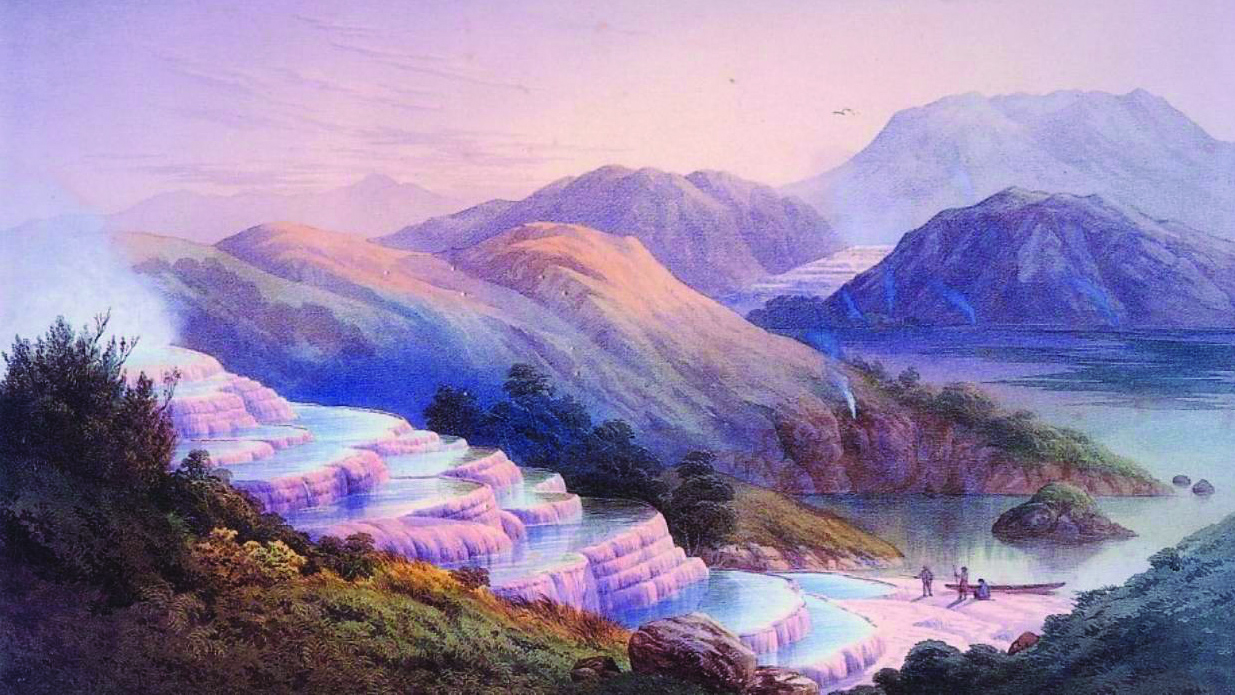

The artist Charles Blomfield did much to preserve the memory of the terraces with his majestic oil paintings.

Blomfield left an evocative account of a working holiday at Lake Rotomahana with his daughter, Mary, at the height of the tourist boom.

Every weekday at about 11 o’clock in the morning, he witnessed groups of “moneyed people” from all parts of the world arrive at the White Terrace and scramble about the glistening silica formations admiring the tiers of basins, while potatoes and koura (fresh water crayfish) were cooked for them in a boiling spring. After lunch the tourists would be conveyed across the lake to the Pink Terrace, where they bathed in its silky waters before heading back to Te Wairoa and a good night’s sleep.

With the afternoon departure of the visitors’ calm descended on the Blomfields beside the lake. Charles often made use of the boiling water for cooking, lowering plum puddings by string into the seething cauldron atop Te Tarata, while Mary hunted for petrified ferns and bird feathers in the mineral pools round about.

The Terraces became New Zealand’s most famous tourist attraction, sometimes referred to as the “Eighth Wonder of the World”.

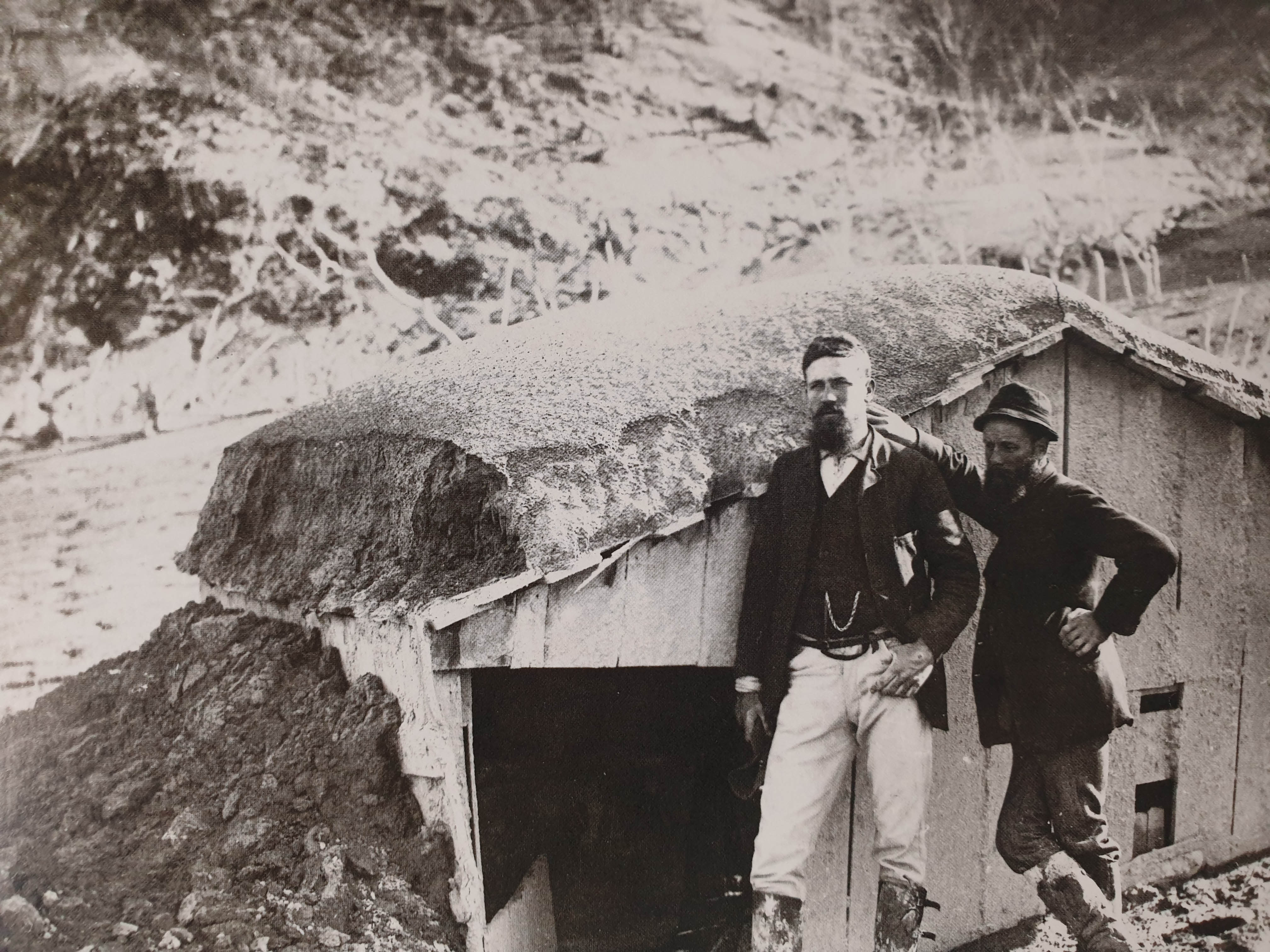

Making the Journey

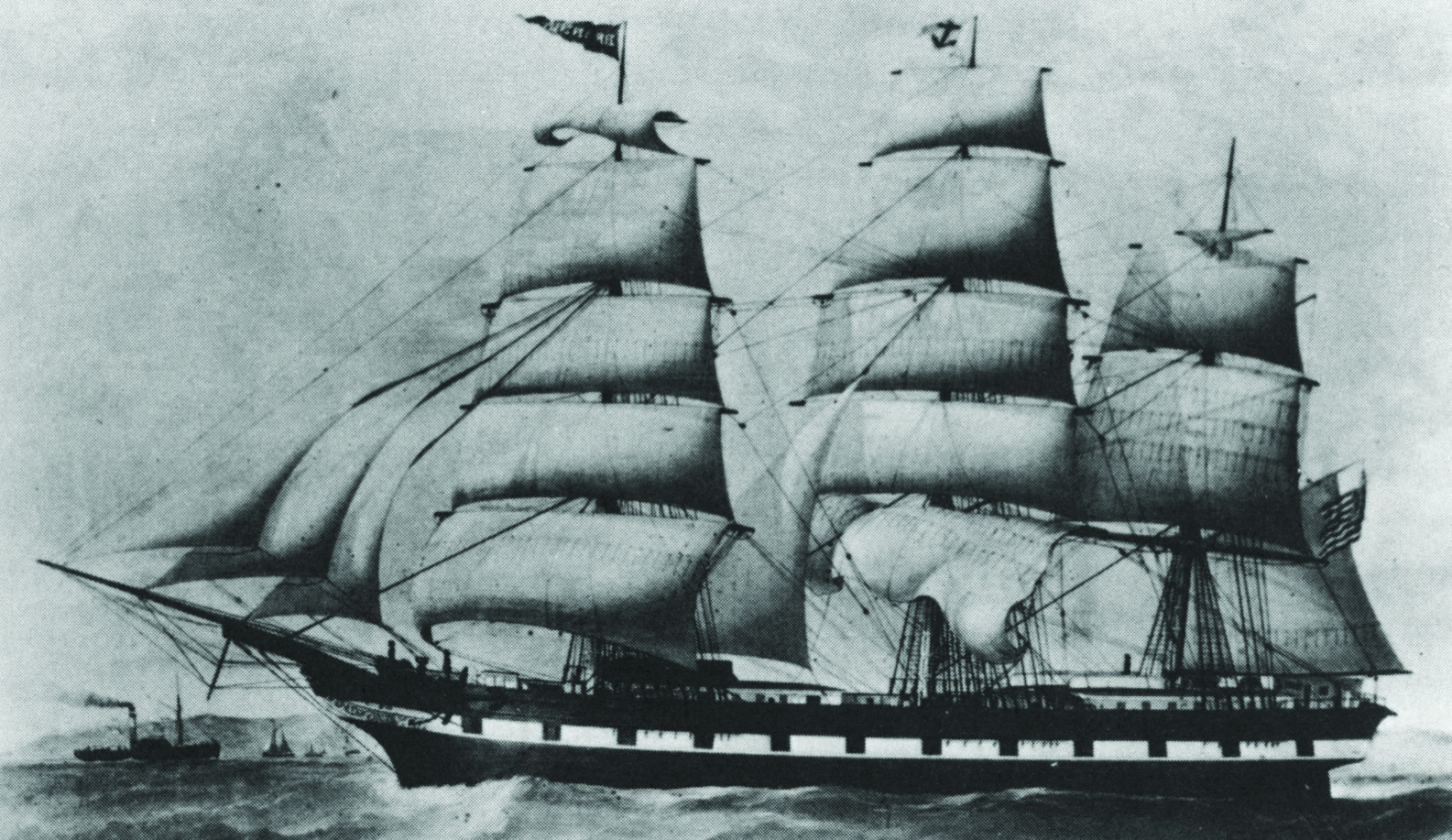

New Zealand was still relatively inaccessible to Europeans and the passage took several months by ship. The journey from Auckland was typically by steamer to Tauranga, followed by a full day stagecoach journey through to Rotorua. The passengers likely assisted in pushing the coach through the deep mud patches on the trip across.

Those who made the journey to the Terraces were most frequently well-to-do, young male overseas tourists or officers from the British forces in New Zealand. The list of notable tourists included Sir George Grey in 1849, Alfred Duke of Edinburgh in 1869, and Victorian novelist Anthony Trollope in 1874.

The first night stay would have been at Ohinemutu on the shores of Lake Rotorua. Arriving at the small resort town, the new arrivals were immediately enveloped by the distinctive odour of hydrogen sulphide and then plugged into a well-rehearsed tourist programme.

The next day, having recovered from their journey and perhaps having sampled the waters of the Rachel or Priest tepid baths, they clambered aboard a coach for the 16 km ride through hill country and the beautiful Tikitapu bush to the village of Te Wairoa, Gateway to the Terraces.

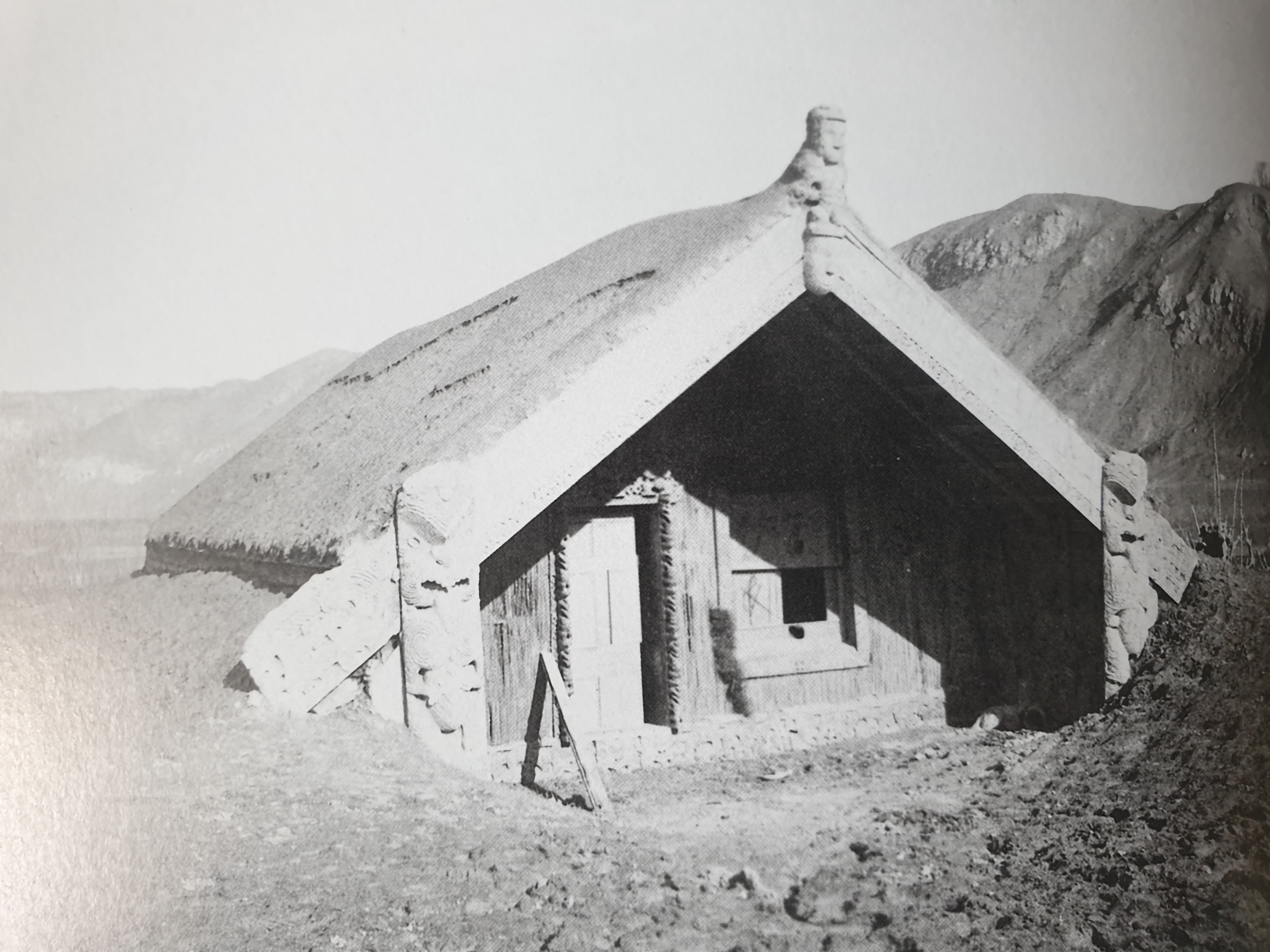

At Te Wairoa visitors were welcomed at several Pakeha (European) hotels and stores, before being treated to a haka and Maori singing in the impressive wharepuni (meeting house) named “Hinemihi”.

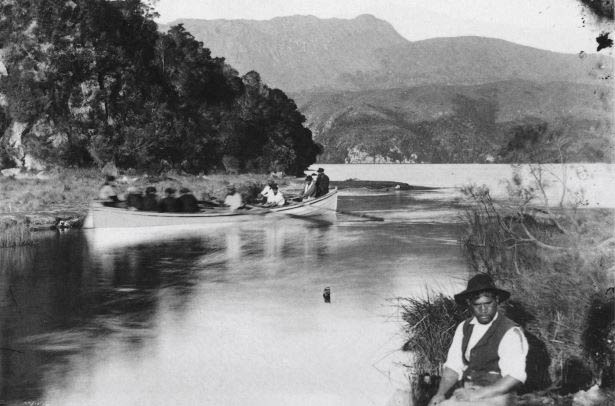

Early the next morning the party (with hotel luncheon, towels, bathing costumes and old footwear for walking around the terraces) made their way by foot to the boathouse on the edge of Lake Tarawera. In canoes or whaleboats, they were transported the 3 hours to the small kainga (village) of Te Ariki, stopping en route to purchase baskets of cherries, potatoes and koura (freshwater crayfish) at another village, Moura, on the headland. A short 20-minute walk through manuka and fern then brought them to the northern tip of sedge-fringed Lake Rotomahana.

The effort to get there was soon rewarded by the sight of Te Tarata, the White Terrace, which appeared as a foaming cascade of water turned to stone. “No wit could possibly conceive or execute anything half as beautiful,” wrote Lieutenant T. M. Jones, of the survey ship HMS Pandora. “The constant pouring of the water over [the basins’] edges has rounded them off in the most graceful curves: the incrustations resembling in many places plumes of ostrich feathers in high relief or the beautiful arabesques to be seen on a frosted windowpane.”

The broad sinter terrace rose in irregular steps 30m from the lake to its summit, where a two-metre-thick rim enclosed a steam-wreathed cauldron of boiling water. The overflow from this pool, cascading down the alabaster staircase, filled each basin in turn, creating an array of baths of decreasing temperature. As the water cooled, deposits of silica built up on the scalloped walls, forming intricate patterns and forcing visitors to wear protective moccasins against the sharp new surfaces.

The narrower Pink Terrace consisted largely of solid shelves of silica. Cupped pools near the top fringed with stalactites and filled with blue water formed delightful bathing chambers.

Recording the Terraces

The appearance of the Terraces was recorded for posterity by a number of photographers. But it was before colour photography was invented and their images lack the enticing colour the formations were known for. Several artists drew and painted the terraces before their loss in 1886, most notably Charles Blomfield, who visited on more than one occasion. The colour chemistry of the Pink Terrace can be seen today at Waiotapu, south of Rotorua, where the Champagne Pool is lined with these same colloidal sulfides.

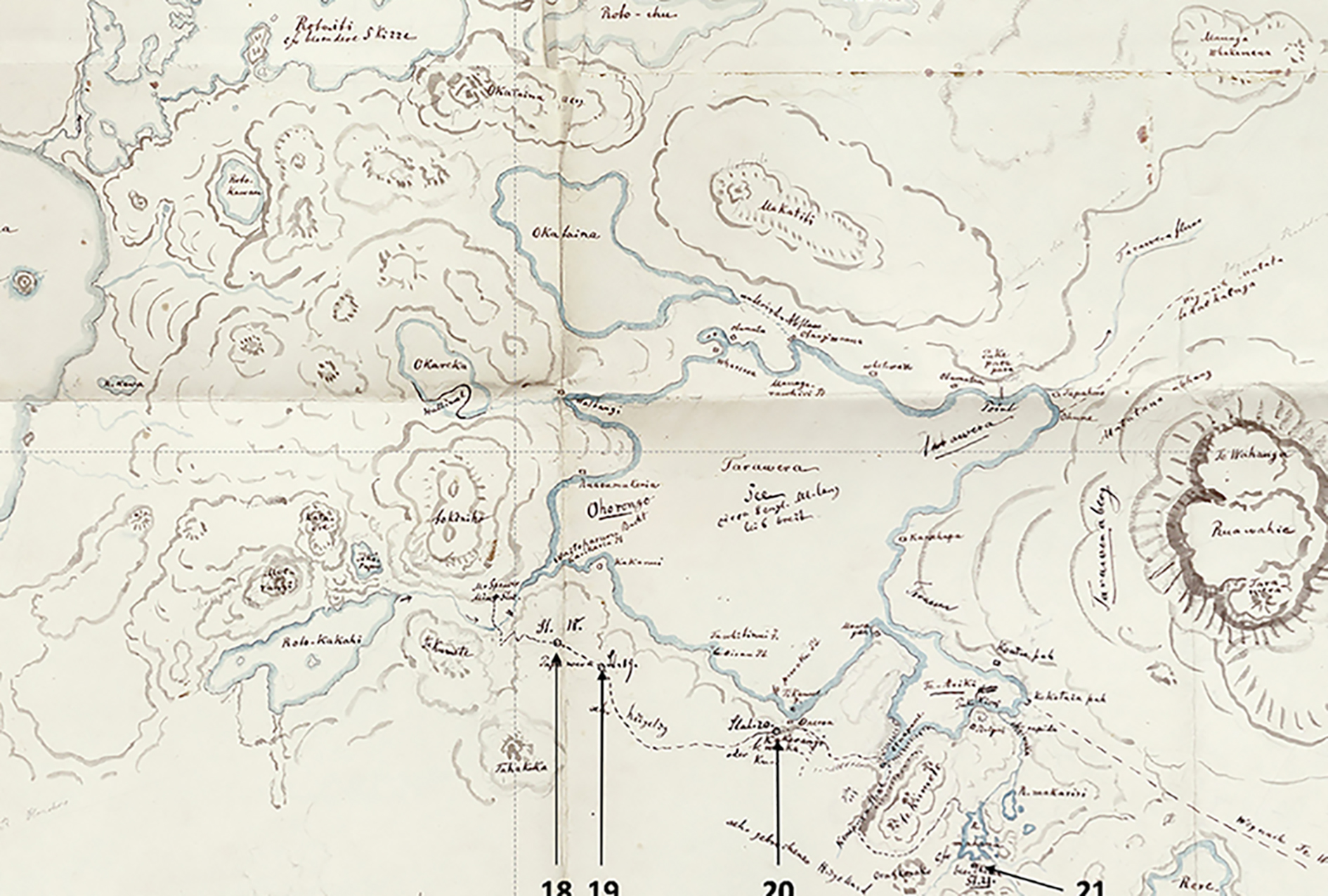

A number of people mapped and commented on the region before the loss of the Terraces. No Maori maps are known. The first colonial sketch map of the lake was by Percy Smith in 1858. Ferdinand Hochstetter carried out the first topographic and geological survey of the Lake Rotomahana area in 1859, producing four maps of the lake while camped on its shore culminating in his defining “Method of Squares” (or Grid) lake map of 30th April 1859.

His lake research was later published in his Geographic and Geological Survey, where the formation of the Terraces was also examined. A commissioned map by August Petermann was included in that work and this was considered valid until 2011, when Sascha Nolden discovered Hochstetter’s original maps in Switzerland and repatriated them to New Zealand in digital form. In 2017 the Hochstetter and Petermann maps were compared and Petermann’s map found defective. Hochstetter’s 1859 map is now considered the more accurate map of Lake Rotomahana.

THE GUIDES

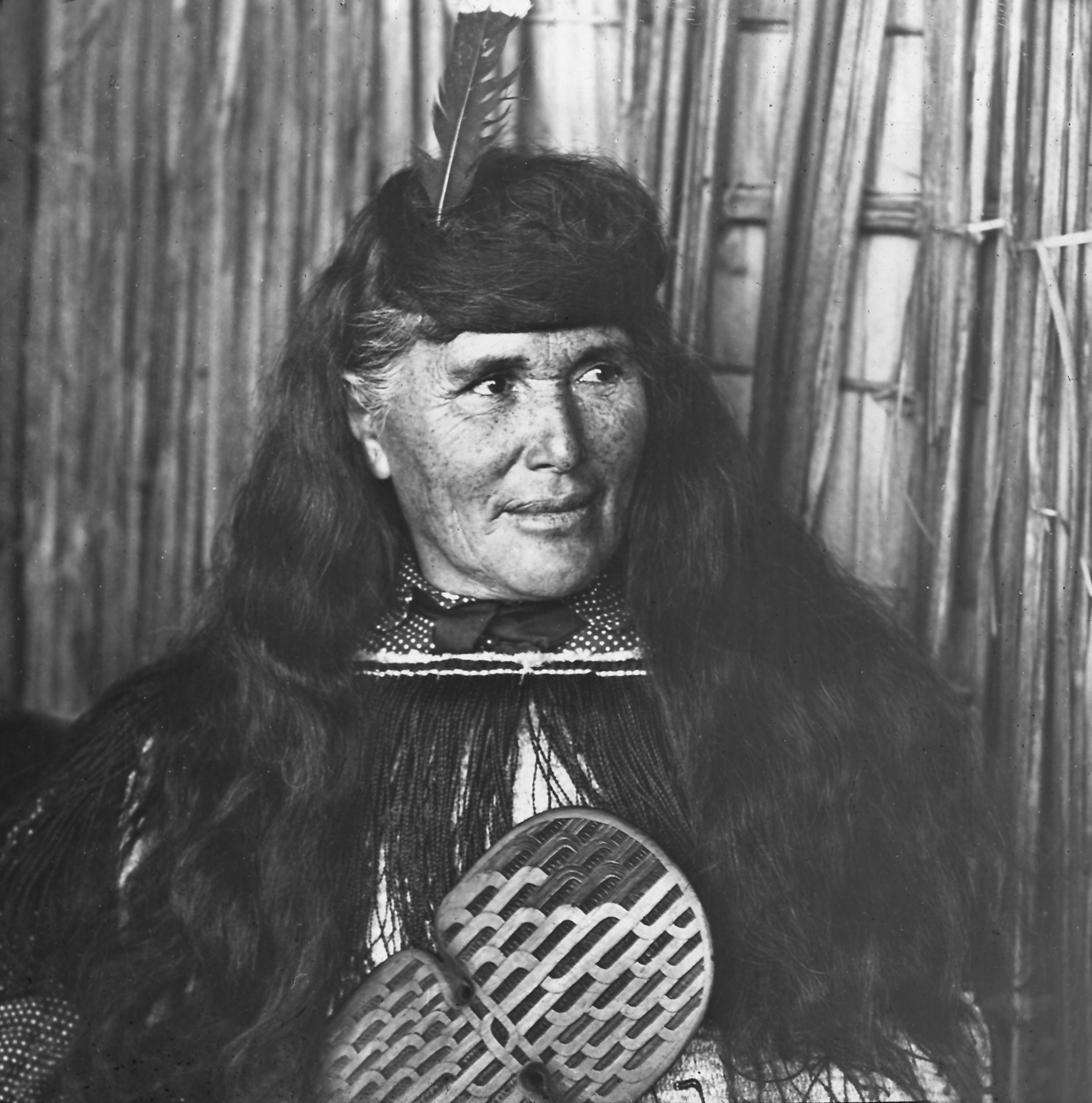

Sophia Hinerangi, sometimes known as Te Paea, took over as principal guide from the older Kate Middlemass in the early 1880s. She became recognised as the principal tourist guide of the Pink and White Terraces. Hinerangi observed the disturbances to Lake Tarawera water levels in the days before the eruption. (Following the destruction of the Terraces during the Mt. Tarawera eruption of 1886, she became a tour guide at nearby Whakarewarewa, Rotorua).

Guide Sophia

Sophia was born in Russell (Kororāreka) in the north of New Zealand in the early 1830s. Her mother, Kotiro Hinerangi, was a Ngāti Ruanui woman who had possibly been captured by a Nga Puhi raiding party. Kōtiro married Alexander Grey (or Gray), a Scotsman who had arrived in the Bay of Islands in 1827. Mary Sophia Gray was baptised by William Williams at Russell (Kororareka) in 1839. It is claimed that Sophia was raised by Charlotte Kemp at the Kerikeri mission station before attending the Wesleyan Native Institution at Three Kings in Auckland.

In 1851 Sophia married her first husband, Koroneho (Colenso) Tehakiroe, with whom it is said she had 14 children. Following her second marriage, to Hori Taiawhio in 1870, she had a further three children. Living at Te Wairoa near the shores of Lake Tarawera, Sophia became a renowned guide to the world-famous Pink and White Terraces. Her husband, Hori Taiawhio was one of the whale boat rowers transporting visitors across Lake Tarawera to the Terraces.

Attractive, well-educated and bilingual, Guide Sophia established a reputation as ‘guide, philosopher, and friend’ to thousands of tourists. Eleven days before the 1886 eruption she was leading a tour group when suddenly the lake level fell, then rose again. This phenomenon was accompanied by an ‘eerie whimpering sound’. Shortly afterwards a phantom canoe appeared with a sole paddler. The canoe grew bigger as it approached the tourists and contained a crew of 13, each with a dog’s head. The ghostly waka then shrank and disappeared. Tuhoto Ariki, a Tuhourangi tohunga, interpreted this as a warning; the exploitation of the Terraces as a tourist attraction showed no regard to ancestral values. Guide Sophia herself saw these omens as a sign that her time as a guide at Rotomahana was nearing its end.

On 10 June 1886, the night of the Mt. Tarawera eruption, over 60 people took shelter in Sophia’s whare (house) at Te Wairoa. Unlike many of the buildings in the village her home withstood the destructive power of the eruption due to its high-pitched roof and strong reinforced timber walls.

Sophia continued her guiding work when she moved to nearby Whakarewarewa Village in Rotorua. In 1895 she joined George Leitch’s Land of the Moa Dramatic Company, playing herself on a tour of Australia. In 1896 she was appointed caretaker of the Whakarewarewa Thermal Reserve. A number of royal parties were amongst the many that Guide Sophia led through Whakarewarewa. She encouraged a number of local women to become guides, helping to establish this occupation as a lucrative form of employment for Tuhourangi women.

Sophia was also heavily involved in the New Zealand Women’s Christian Temperance Union, becoming president of the Whakarewarewa branch in 1896.

Guide Sophia died at Whakarewarewa on 4 December 1911.

Phantom Canoe – Devastating Prediction

Guide Sophia herself had alluded to several premonitions as she had accompanied Charles Bainbridge by boat over Lake Tarawera. Just the previous week she had been on the lake with a party of sightseers when they had seen a canoe in the distance. As it drew closer it seemed to grow to the dimensions of a war canoe. The paddlers increased in number and, to Sophia’s horror, they appeared—in at least one version of her story—to possess the heads of dogs. As she watched, the deathly waka (canoe) shrank before disappearing into the waters of the lake.

The appearance of what came to be called the “phantom canoe” was not an isolated event. Before setting out that day, Sophia and her group had been surprised to find the Wairoa Creek dry at the landing with the boats beached on the mud. As they watched, the water twice surged up the channel “with a crying, moaning sound” and refloated the craft, before draining away again and dropping the hulls back onto the creek-bed.

The incident had rattled some in the party, but the Maori boatmen, keen to get their fee for conveying the passengers to Te Ariki, had persuaded the group to go on. It was midway through the journey and under a clear sky, that the spectral canoe had been sighted not half a kilometre distant and being paddled hard.

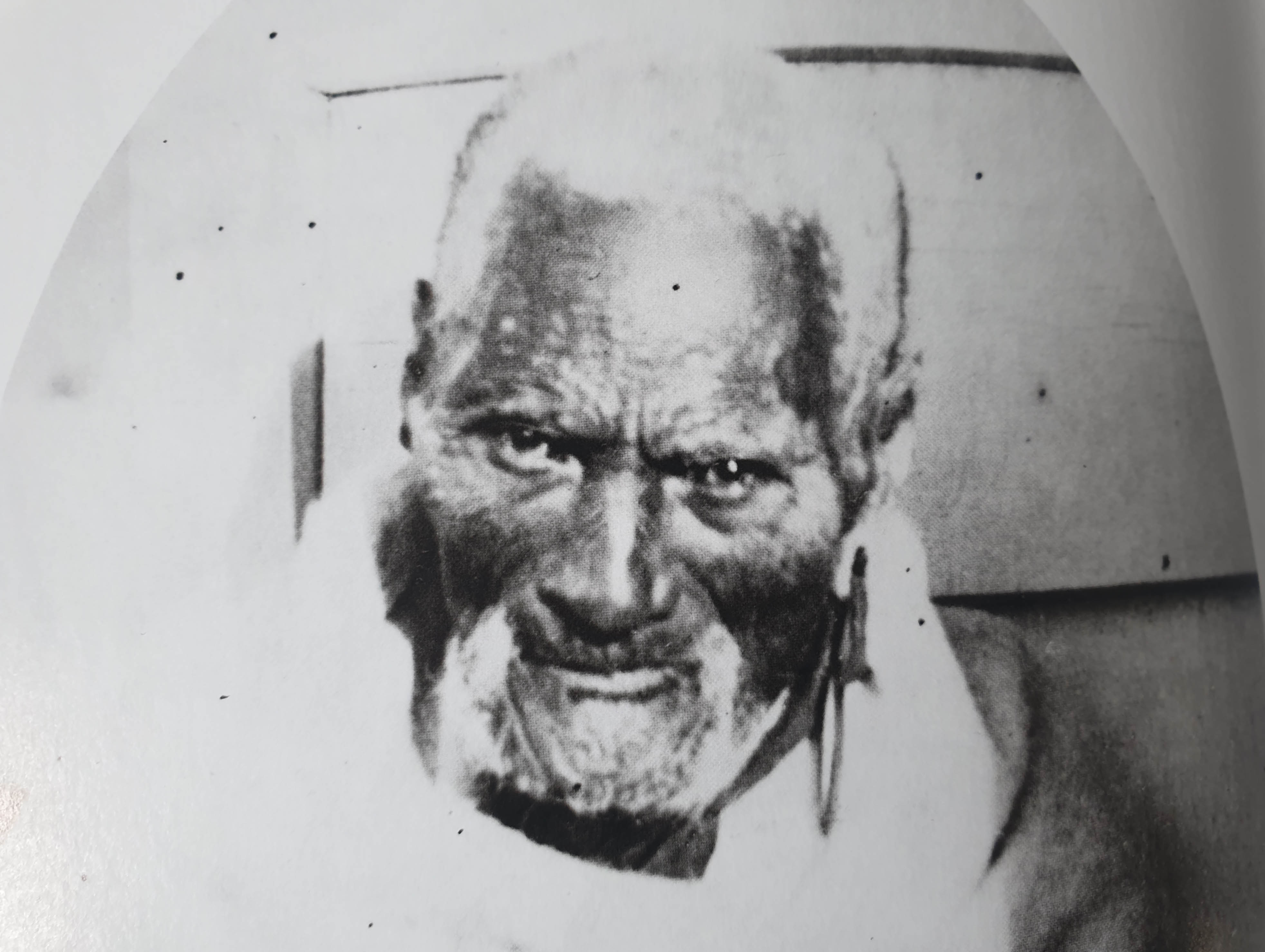

At the terraces an old chief, Rangiheuea, interpreted the omens as indicating that a big war was brewing. At Te Wairoa the ageing tohunga, Tuhoto Ariki, when asked for his opinion, declared that the apparition on the water foretold that the entire region would be overwhelmed.

Tuhoto’s prophecy of doom was attributed to his anger at the effects of tourism on the local Tuhourangi people. No visitor to Te Wairoa could deny the changes it had brought. Froude wrote scathingly: “The influx of foreign gold had here, as often elsewhere, proved more of a curse than a blessing. The drunkenness and vice . . . was nowhere so rampant as at Wairoa. The usual restraints of religion went for little here.”

Froude certainly took exception to the ease with which the local Maori relieved Pakeha (Europeans) of their money. The customary placing of a token (peaches, for example, or a fern branch) on a rock near Moura in the hope of fine weather, had been gradually transformed into an obligatory tourist donation. “The gentleman to whom the money is entrusted jumps up the rock with it and disappears for a second, then strikes the rock, utters some gibberish, and comes down again with the coin in his pocket or boot, to be converted into rum on the first opportunity,” he wrote.

Other travellers, less blinded by class divisions and perhaps more admiring of commercial enterprise, thought the Maori splendid both as guides and companions. There could be no doubt of the result, however.

The Terraces had brought a great deal of wealth to Te Wairoa, a former centre of missionary activity. Charges for boat journeys, photography, sketching and entertainments brought in an estimated £1800 a year, at a time when an Auckland–hot lakes (what is a hot lakes trip?) round trip cost £5. Despite the wealth (even the shells in the carvings of the meeting house “Hinemihi” were replaced by gold coins) the 120 or so Maori of Te Wairoa were far from unconcerned, even before the appearance of the ghostly canoe. The community had suffered a seemingly unending succession of deaths over recent months, some from typhoid, and tangi (funerals) had become an almost daily occurrence. Just days before Bainbridge’s arrival in Rotorua, the editor of the Waikato Times had appealed to the government to investigate the causes of the disturbing mortality rate.

Given this climate of misfortune, Tuhoto’s damning prediction carried an awful ring of truth. Furthermore, in the summer just gone, the flax had failed to flower, which was interpreted as portending a big earthquake. Some locals may also have recalled the words of Te Kooti, who earlier that year, had been the guest of Rangiheuea. As he was leaving, the warrior prophet reportedly turned to his host and said: “Take my advice and clear out of this place. Something is going to happen, I cannot tell you when it will happen—it may be soon, or it may be late—but come it will.”

Not far from the blacksmith’s workshop is Tuhoto’s whare. The remarkable old tohunga who had caused such consternation with his dire prophecies, was buried here by the eruption. Many Maori, believing him in some way responsible for the calamity, feared that disturbing his resting place would only bring new misfortune.

Some days after the eruption and despite such misgivings, several Pakeha decided that they should recover the tohunga’s body. He had survived for four days.

TE WAIROA (THE BURIED VILLAGE)

The town of Te Wairoa was founded in 1848 to service tourists who were on their way to see the world-famous Pink and White Terraces. They came from Europe by ship, steamer, coach, horseback, foot and finally canoe to marvel at their beauty. They were guided by local people.

Te Wairoa village on the western shore of Lake Tarawera was the home of Tuhourangi, a 150-strong sub-tribe of Te Arawa. As early as the 1840s, a few hardy tourists had slogged through the bush on foot or horseback to see the incredible Pink and White Terraces on Lake Rotomahana, but the trickle turned to a flood after a road from Rotorua to the embarkation place at Te Wairoa was built in 1875.

By the beginning of the 1880s, the meeting house “Hinemihi” had been completed and two hotels built, and Te Wairoa was becoming something of a tourist hub. The village had a school, a church and a cemetery, three stores and a Temperance Hall. An experienced boatbuilder was engaged to make whaleboats for the tourist trade to replace the traditional canoes.

Te Wairoa was destroyed by scoria ash, mud and rockfall and finally abandoned after the eruption of Mount Tarawera on the 10th of June 1886.

THE ERUPTION

It was a way of life that was to end abruptly in the early hours of June 10, 1886. Without warning, Mount Tarawera became violently active and in the hours that followed a choking layer of scoria, ash and mud buried the surrounding landscape. Many of the villages close to the mountain disappeared without trace and the Pink and White Terraces, the livelihood for so many, were obliterated. For the Tuhourangi people these were hours of loss and total devastation. Around 150 people lost their lives. Maori believed that many more had perished that night. The exact number of casualties has never been determined.

Family members took in eruption survivors at the little village of Whakarewarewa located in central Rotorua. Whakarewarewa was becoming a popular tourist destination in its own right for its geothermal activity. Most of the Tuhourangi homeless eventually settled at Whakarewarewa, where they were able to rebuild their lives and continue welcoming visitors to experience Rotorua’s natural wonders.

For Maori Mount Tarawera consists of 3 mountains – from the left Wahanga, centre Ruawahia and right Tarawera. The eruption spread from west of the Wahanga dome, 5 kilometres (3.1 miles) to the north and down to Lake Rotomahana. The volcano belched out hot mud, red hot boulders, and immense clouds of black ash from a 17 kilometres (11 mile) rift that crossed the mountain, passed through the lake and extended beyond into the Waimangu Valley.

After the eruption, a crater over 100 metres (330 ft) in depth encompassed the former site of the terraces. After some years this filled with water to form a new Lake Rotomahana, 30–40 metres (98–131 ft) higher, ten times larger and deeper than the old lake.

THE TUHOURANGI STORY CONTINUES

Shortly after the eruption dispossessed Tuhourangi were invited to live at Whakarewarewa by a closely related hapu, Ngati Wahiao.

Having developed a liking for thermal springs, while enjoying temporary shelter at Ohinemutu, the majority of Tuhourangi overcame their new-found mistrust of vulcanism and took up the offer. Sophia herself spent the last 25 years of her life at Whakarewarewa, guiding people around the village until her retirement, and even thereafter happily welcoming visitors who wished to talk.

Today we have returned to Lake Tarawera to resume our occupation of our ancestral lands. One third of the land surrounding Lake Tarawera and Lake Rotomahana is still owned by Tuhourangi and Ngati Rangatihi tribes, while much is now under Department of Conservation management.

For many years after the eruption Tarawera was seen as a burial ground and members of the tribe were discouraged from the reoccupation of this area.

Now Totally Tarawera is a tribal business proud to be back honouring our land and sharing our stories and history with our guests from New Zealand and around the world.

OUR MOST POPULAR EXPERIENCES

Find Us

on Maps

We are located in Mariners House, on Tarawera Road, above The Landing Cafe.

It’s around a 15 minute drive from Rotorua Central, past the Redwood Forest and Blue Lake.

Mariners House, Tarawera Road,

Lake Tarawera, Rotorua, New Zealand

Latitiude: -38.20624787242264

Longitude: 176.37411476760258

info@totallytarawera.com

+64 7 362 8080